Six years after the disaster, many buildings still sit abandoned in Naraha, a town in the Fukushima prefecture that was evacuated after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Work is underway to demolish old and contaminated buildings to make way for new ones.

Children play in a dirt lot on the coastal town of Hisanohama. The city is still working to rebuild the homes and businesses that were destroyed by the tsunami.

After all the other buildings on the coast of Hisanohama were swept away by the tsunami, this shrine was the only structure still standing.

Kiyoko Shiga, 88, and her two children, were forced to evacuate from their home in Naraha when the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant experienced a triple meltdown following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. Along with many other evacuees, they are still living in temporary housing.

Kiyoko Shiga sits on the floor in the living room of her temporary housing while her son and daughter talk about their experiences as nuclear evacuees.

Kiyoko Shiga lived in Naraha for over 60 years. Family photos are the only memories she has to remember her longtime home.

Fisherman Tomo Komatsu and his mother, Hatsui Komatsu, sit in their living room with their dog Marine. Hatsui has lived in her house in Nakoso for more than 60 years. She has other children but they have moved away. Tomo Komatsu has stayed to take care of her and to keep his job as a fisherman, even though he can no longer sell the fish he catches.

A group of fishermen from Nakoso pull in a net full of translucent sardines. They have not been able to sell the fish they catch since the nuclear disaster on 3.11, but every Monday they catch fish to test them for radiation.

Each week, fishermen in Nakasogyoko, a small port on the southern border of Fukushima Prefecture, receive a stipend to catch fish for data.

"I worry that even when radiation is low and I can sell my fish, customers won’t buy because the name Fukushima will be on the package," Tomo Komatsu said. On work days, he wakes up at 5 in the morning and eats breakfast with his 92-year-old mother. They keep a calendar in the living room of their small wooden house with every Monday circled in permanent marker.

Naoto Matsumura, 58, refused to leave when Tomioka was evacuated. He was born there, and except for a time in his 20s, has always lived in this small town. Now, it’s abandoned, but he remained, caring for animals that were left behind when the 3.11 triple disaster occurred. He risks being exposed to radiation by living here but said he stays for the animals: “I can’t just throw their lives away.”

One of Matsumura's homes on the property remains in shambles. It was shaken by the quake but much of the damage is a result of wild bores.

Matsumura wears a bright blue jumpsuit and smokes 30 cigarettes a day. His house is filled with bottles of whiskey and beer, packaged food, piles of paper and a collection of cranes from an anti-nuclear rally in France.

When he first began taking care of the animals, Matsumura struggled to get feed that wasn't contaminated. Next to the pasture lay bags of garbage from feed.

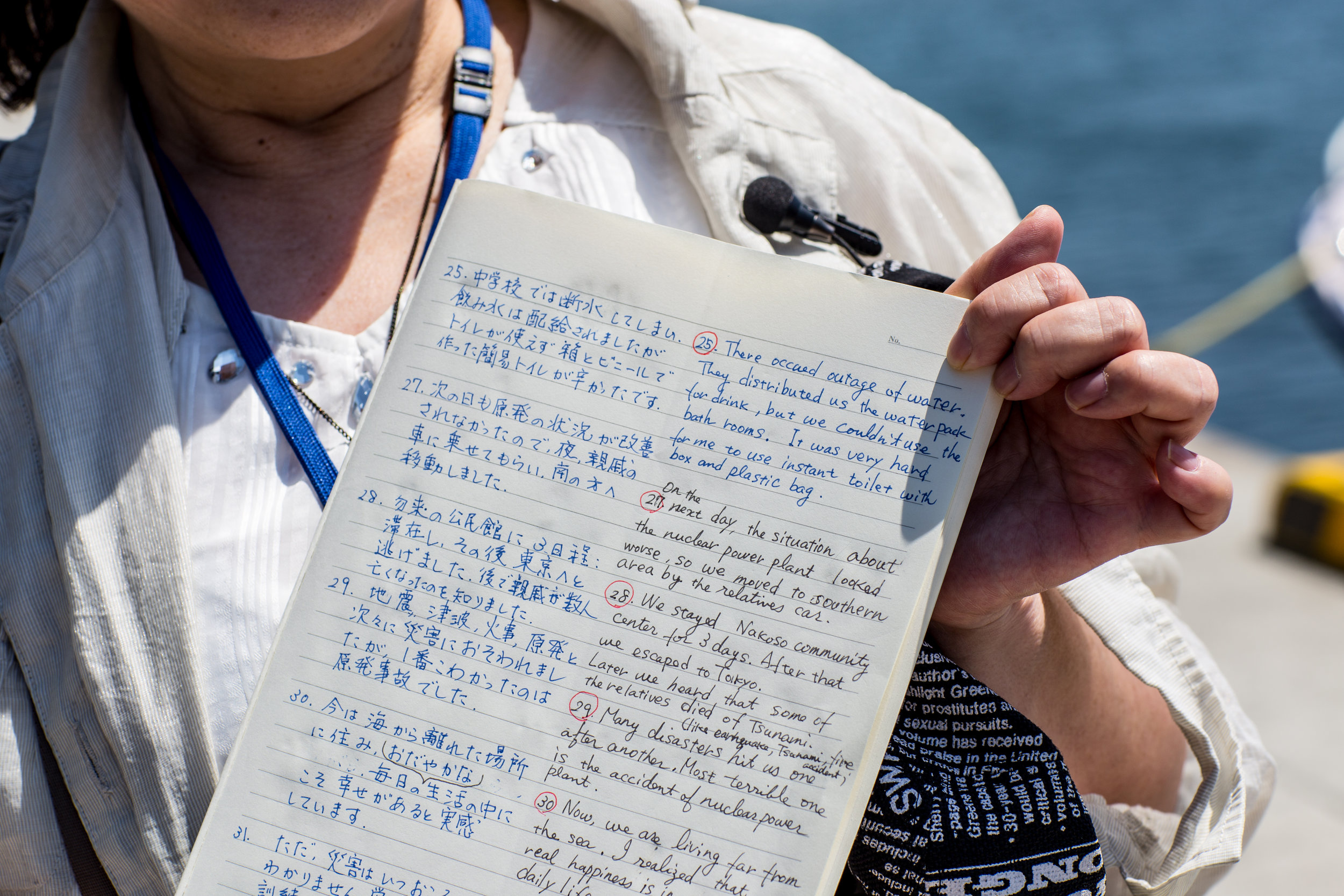

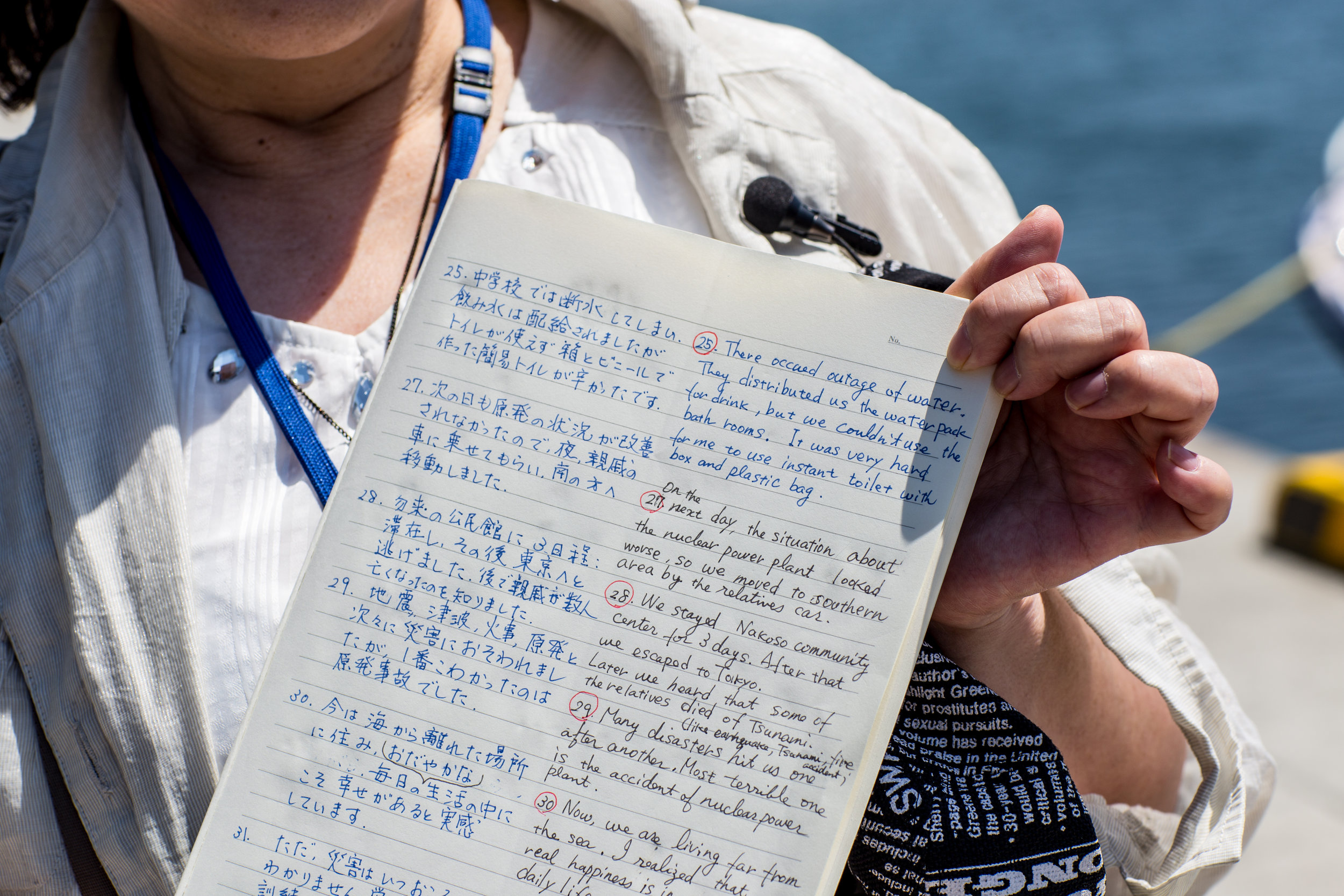

Chiyuki Kimura, a translator, was at her home in the coastal city of Hisanohama when the earthquake struck. She has written her story in Japanese and English so that she can remember what happened that day and share her story with people she meets.

An abandoned bowling alley inside the no-go zone. Buildings, homes and cars were abandoned after the triple disaster. Inside the no-go zone it feels as if time has stopped.

Naraha has been at the heart of media coverage since it was the first town to lift the post-disaster evacuation order in 2015. The town piqued the interest of people around the world once again, in April 2017, when it opened a new elementary and junior high school and invited families and children to come home.

But as the media focused its attention on the new school, the principals fought to protect their students. Evacuees are stigmatized by those outside the nuclear fallout zone, and school leaders closely guard the identity of these children. They don’t want their students to be traumatized again by discrimination.

Inside of the no-go zone gates have been placed in front of homes to prevent people from returning or visiting.

Six years after the disaster, many buildings still sit abandoned in Naraha, a town in the Fukushima prefecture that was evacuated after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Work is underway to demolish old and contaminated buildings to make way for new ones.

Children play in a dirt lot on the coastal town of Hisanohama. The city is still working to rebuild the homes and businesses that were destroyed by the tsunami.

After all the other buildings on the coast of Hisanohama were swept away by the tsunami, this shrine was the only structure still standing.

Kiyoko Shiga, 88, and her two children, were forced to evacuate from their home in Naraha when the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant experienced a triple meltdown following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. Along with many other evacuees, they are still living in temporary housing.

Kiyoko Shiga sits on the floor in the living room of her temporary housing while her son and daughter talk about their experiences as nuclear evacuees.

Kiyoko Shiga lived in Naraha for over 60 years. Family photos are the only memories she has to remember her longtime home.

Fisherman Tomo Komatsu and his mother, Hatsui Komatsu, sit in their living room with their dog Marine. Hatsui has lived in her house in Nakoso for more than 60 years. She has other children but they have moved away. Tomo Komatsu has stayed to take care of her and to keep his job as a fisherman, even though he can no longer sell the fish he catches.

A group of fishermen from Nakoso pull in a net full of translucent sardines. They have not been able to sell the fish they catch since the nuclear disaster on 3.11, but every Monday they catch fish to test them for radiation.

Each week, fishermen in Nakasogyoko, a small port on the southern border of Fukushima Prefecture, receive a stipend to catch fish for data.

"I worry that even when radiation is low and I can sell my fish, customers won’t buy because the name Fukushima will be on the package," Tomo Komatsu said. On work days, he wakes up at 5 in the morning and eats breakfast with his 92-year-old mother. They keep a calendar in the living room of their small wooden house with every Monday circled in permanent marker.

Naoto Matsumura, 58, refused to leave when Tomioka was evacuated. He was born there, and except for a time in his 20s, has always lived in this small town. Now, it’s abandoned, but he remained, caring for animals that were left behind when the 3.11 triple disaster occurred. He risks being exposed to radiation by living here but said he stays for the animals: “I can’t just throw their lives away.”

One of Matsumura's homes on the property remains in shambles. It was shaken by the quake but much of the damage is a result of wild bores.

Matsumura wears a bright blue jumpsuit and smokes 30 cigarettes a day. His house is filled with bottles of whiskey and beer, packaged food, piles of paper and a collection of cranes from an anti-nuclear rally in France.

When he first began taking care of the animals, Matsumura struggled to get feed that wasn't contaminated. Next to the pasture lay bags of garbage from feed.

Chiyuki Kimura, a translator, was at her home in the coastal city of Hisanohama when the earthquake struck. She has written her story in Japanese and English so that she can remember what happened that day and share her story with people she meets.

An abandoned bowling alley inside the no-go zone. Buildings, homes and cars were abandoned after the triple disaster. Inside the no-go zone it feels as if time has stopped.

Naraha has been at the heart of media coverage since it was the first town to lift the post-disaster evacuation order in 2015. The town piqued the interest of people around the world once again, in April 2017, when it opened a new elementary and junior high school and invited families and children to come home.

But as the media focused its attention on the new school, the principals fought to protect their students. Evacuees are stigmatized by those outside the nuclear fallout zone, and school leaders closely guard the identity of these children. They don’t want their students to be traumatized again by discrimination.

Inside of the no-go zone gates have been placed in front of homes to prevent people from returning or visiting.